Stress and pressure seem to be ever-present these days. And when you work in a fast-paced work environment like Octopus, finding ways to survive and thrive under pressure is essential.

We’re currently using behavioural science to help our employees deal with pressure and stress at work more effectively, with the aim of producing sustained benefits to health, wellbeing and performance.

Rob Archer is a Chartered Psychologist who specialises in resilience training, working with business executives, front line staff and sportspeople across the world. Rob has been brought in to help Octopus employees manage their performance at work, recognise the triggers that cause stress, and to develop more positive ways of dealing with it.

‘Good’ vs ‘bad’ stress

For most of us, pressure and stress are largely helpful for both health and performance. If you think about the best moments of your life (passing exams, getting married, having children, for example), many are bound up with an element of pressure or stress. The stress response is a useful and reliable way of galvanising us into action and it has played a big part in our survival for millennia. So, we’re well-equipped to deal with short-term (acute) stress.

However, we’re much less capable of coping with prolonged or chronic stress; the type which is lower level but more persistent. Many people today find themselves experiencing chronic stress at work due to workload, home pressures, or an inability to switch off. Some also experience chronic stress because they feel conflicted or guilty about taking time to recover.

Stress, therefore, is not the problem as such. Chronic stress is the problem. If we don’t address the causes of chronic stress it has profound effects for health, wellbeing, and our ability to perform at our best.

What are some of the most recognisable responses to stress at work?

- Losing focus on tasks and becoming overwhelmed by competing priorities.

- Inability to solve problems, even relatively simple ones.

- Instantly reacting and making poor decisions as a result.

- Thinking rigidly, for example over-generalising or becoming overly pessimistic.

- Passing on your stress to others – either by lashing out or ‘clamming up’.

There are also issues that stem from the ways we try to cope with stress, such as reaching for ‘quick fixes’ like sugar or caffeine, staying static for too long at our desks, sleeping less, doing too many things at once (studies show that multitasking is far less efficient and uses far more energy than focusing on single tasks) and working longer hours – with fewer breaks – to make up for the loss in performance.

The problem is that these responses put us at risk of increasing our stress levels still further. Performance inevitably suffers and there can be a tendency under pressure to ‘just plough on’ and ignore the early symptoms. But this rapidly impairs cognitive performance, so we find ourselves working harder for the same results.

Beware rigid thinking

One of the most damaging characteristics of chronic stress is that it changes the way we think. We become more rigid in our thinking and increasingly fail to notice other perspectives. In many cases, the mental shortcuts that we use to make decisions start to generalise. We start to ‘fuse’ with our thoughts, and eventually this leads to much less flexible responding and narrow, rigid behaviour responses.

Look out for ‘mind traps’

Mind traps are common examples of mental shortcuts that can be helpful in some scenarios, but which become less helpful when they becomes fixed or rigid. Here are some examples:

- Focusing on the ‘worst case scenario’ in most situations.

- Thinking that everything people do or say is some kind of reaction to you personally.

- Getting upset that life is not how you believe it should be, or where your demands are not being met.

- Thinking that you already know what others are thinking and feeling, without them saying so. Also expecting others to know how you feel, without you communicating with them.

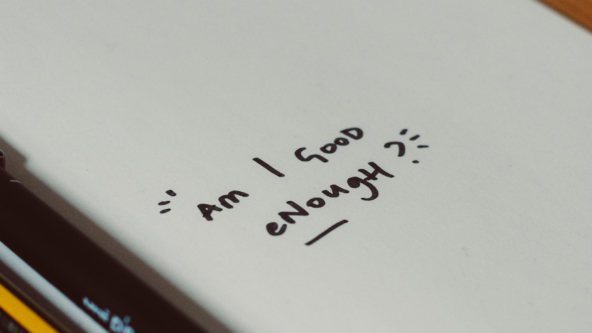

- Expecting or demanding perfection (from yourself or other people around you) and seeing it as a total failure if falling short.

None of these ways of thinking is ‘wrong’, but if we fuse to them too rigidly they can start to drive counterproductive behaviour. The best defence against mind traps is to be aware of them and in particular to notice when they start to drag you into unhelpful behaviours.

“A quick and easy way to move from unhelpful, emotion-focused mind traps into more helpful solution-focused thinking is to practice perspective-taking.”

Rob Archer, Chartered Psychologist

When you find yourself feeling stressed, try to notice whether you have fallen into a mind trap. You can then get some perspective on your situation by asking yourself:

- Is there another way of looking at the situation?

- Is this thought helpful to your long-term objective?

- What you would you tell a close friend if they were in your situation?

- And finally, what do you choose to do next?

Choosing the best way forward

The key to stressful events is to remember that you always have a choice; not necessarily over how you react with your thoughts and emotions, but how you respond with your actions.

“A ‘positive attitude’ does not necessarily involve being or feeling positive. It means developing the ability to choose our response to stressful situations.”

Rob Archer, Chartered Psychologist

Manage the instant reaction and consciously choose your response

In the US military they have a saying: “slow is smooth, smooth is fast”. Resisting the temptation to react quickly and consciously choosing your response means you’re giving yourself the time to come up with better alternatives that could help you to achieve a more positive outcome.

Try to bring your attention back to your response to the situation. You might not be able to control everything in the situation or make any big changes immediately. But see if you can identify small, achievable changes which will help give you a small payoff and some sense of control. We tend to overestimate the need for big changes and underestimate the surprising power of these behavioural ‘marginal gains’. By making small changes, most people feel this also frees up energy for further changes down the line.

Instead of the vicious circle of chronic stress, we start to reconnect to a more natural and sustainable model of high performance under pressure.

Key points when you’re in a stressful situation

- Remember – recovery is the foundation of performance. Stressful situations demand you be at your best. Try to identify regular recovery periods on a daily, weekly, monthly and annual basis.

- Be aware that your instant reaction is not always the most helpful, especially if you are looking for long-term results or creative solutions.

- Practice noticing ‘mind traps’ and watch out for fused or rigid thinking.

- Think about what you would advise a close friend to do in the same situation.

- Focus on one task at a time instead of being drawn into multitasking.

- Stay hydrated and do what you can to maintain stable blood sugar levels.

- Integrate exercise and movement into your life and work routine.

- Commit to small behavioural experiments – behavioural marginal gains – that help you stay agile in the face of stress.