Last November’s Industrial Strategy White Paper saw the UK Government setting out ambitious plans for clean growth in the UK. From creating a bioeconomy to enforcing stricter energy efficiency, the measures aim to lay the groundwork for a sustainable future.

Energy is changing

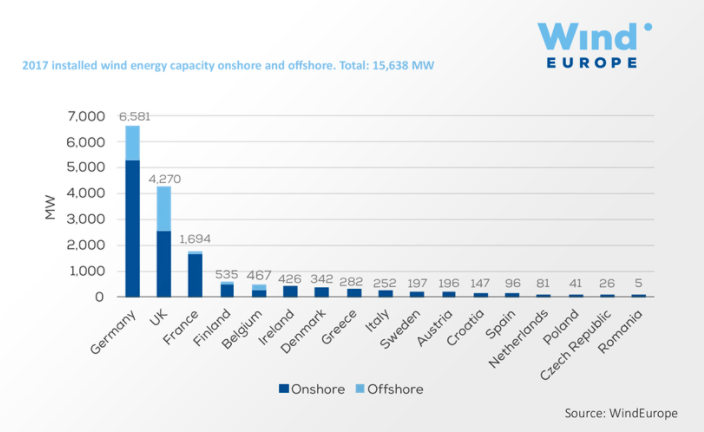

The UK has made enormous progress towards decarbonising its energy supply. Renewable energy accounted for 29.4% of the UK’s energy generation in 2017 – a record year. Wind is one of our biggest successes, with generational capacity increasing 22% over the last three years. Solar capacity grew 7% in the last year, and is expected to climb further as falling technology costs and market forces compensate for reduced government subsidies.

An industry of the future

The renewable industry is booming. It employed 208,000 full-time equivalents in 2016 (in the UK), an increase of 3.3% over the previous year. Over the same period, the UK’s oil and gas employment figures dropped almost 16% to 302,200 (and has dropped every year since 2013).

Open competition will promote further growth, reduce unemployment, and offer rewarding career paths for science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) students, like those we met at Bridlington School in Yorkshire.

Our Renewable Investments Team, for example, has helped Octopus grow to become one of the largest solar developers in the world. And Octopus Energy, our energy supply business, ensures year-round renewable electricity through a complement of solar, wind, and anaerobic digestion (making energy from waste) sites.

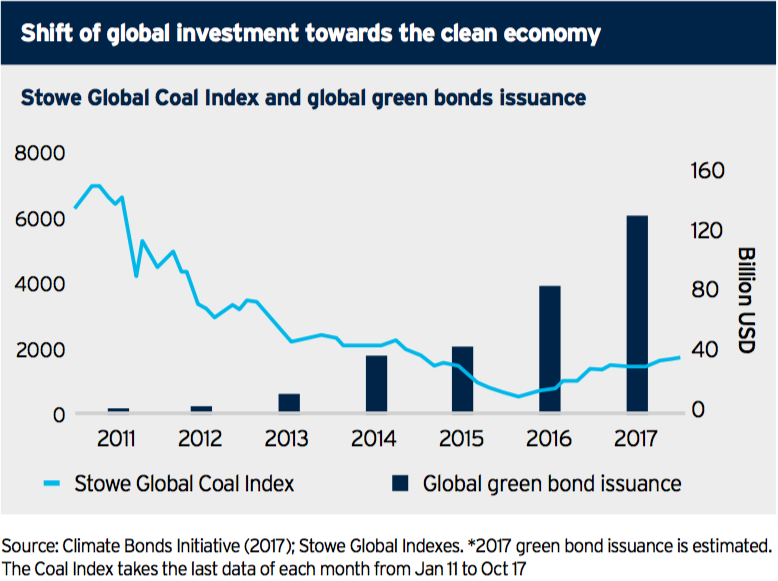

Our decarbonising economy is creating new jobs, employing more people, and creating exciting investment opportunities that will help realise the government’s plans for a sustainable future, without the need for subsidy. But the government must favour an open market based on innovation and efficiency otherwise progress will be awkward and slow.

A fairer deal for consumers and businesses

Of course, while open competition and better infrastructure are important, they don’t address the failures of the consumer energy market.

For too long, “tease and squeeze” pricing has skewed the market in favour of large, cumbersome suppliers that draw in customers on cheap fixed deals and switch them to expensive Standard Variable Tariffs (SVTs) a year later. Unless the government imposes a relative price cap between the deal price and SVT, those who don’t switch every year will pay too much for their energy.

Price isn’t the only concern, however, and the government has promised to help consumers and businesses use less energy by becoming more efficient. One way it intends to do this is by tightening rules on Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs). This will make it easier to rent properties that are energy efficient, and bans renting properties rated lower than Band E. Similarly, the government is helping some of the most energy-intensive industries reduce their energy consumption, without impacting growth, as part of their 2050 Industrial Decarbonisation and Energy Efficiency Action Plans.

The Industrial Strategy white paper is an encouraging vision of a cleaner, greener Britain. However, for these plans to work, the government must support emerging technologies through open competition, better infrastructure, and a fairer market for energy consumers.